Capt Thomas Grover

Shays Rebellion, 1786-1787 - A very poignant history lesson that has much relevance today.

Shays' Rebellion, the post-Revolutionary clash between New England farmers and merchants that tested the precarious institutions of the new republic, threatened to plunge the "disunited states" into a civil war. The rebellion arose in Massachusetts in 1786, spread to other states, and culminated in the rebels' march upon a federal arsenal. It wound down in 1787 with the election of a more popular governor, an economic upswing, and the creation of the Constitution of the United States in Philadelphia.

Shays' Rebellion "had a great influence on public opinion," as Samuel Eliot Morison notes; it was the fiercest outbreak of discontent in the early republic, and public feeling ran high on both sides. After the rebellion was defeated, the trial of the insurgents in 1787 was closely watched and hotly debated.

- For a long time, traditional historians were content to portray the rebels as wrongheaded villains in an unfolding drama of patriotism. Recent historians have revolutionized our understanding of early American family and community life, and improved our comprehension of post-Revolutionary political and social struggles.

-

- To follow Shays' Rebellion is to witness an escalating crisis in which the men who fought or financed the American Revolution were obliged to reconsider that revolution and its principles only ten years later.By the year 1786, the "disunited states" (as the Tories liked to call them) had achieved political independence -- but the eastern states seemed on the verge of collapse as the flames of civil war menaced New England.

-

-

The American revolution, it seemed, had almost gone too far. General George Washington wrote:

Others in the political elite held the same opinion -- even Massachusetts' onetime Revolutionary agitator, Samuel Adams:"I am mortified beyond expression when I view the clouds that have spread over the brightest morn that ever dawned in any country... What a triumph for the advocates of despotism, to find that we are incapable of governing ourselves and that systems founded on the basis of equal liberty are merely ideal and fallacious."

Only the young Thomas Jefferson -- reflecting more philosophically and from a safe distance in Europe -- disagreed:"Rebellion against a king may be pardoned, or lightly punished, but the

man who dares to rebel against the laws of a republic ought to suffer death."

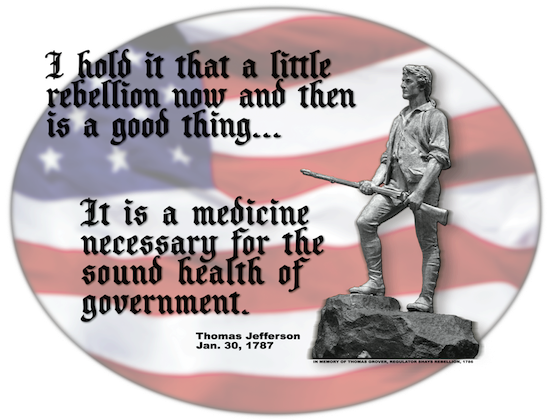

All eyes were on Massachusetts, where the insurgents who called themselves "Regulators" or "Shays men" had brought about riots, raids, and the closing of courts."A little rebellion now and then is a good thing. It is a medicine necessary for the sound health of government. God forbid that we should ever be twenty years without such a rebellion."

New England's agrarian way of life, which furnished a subsistence and social structure for the rural majority, was independent-minded, community-oriented and traditional in its economy and cultural values. -

New England's merchants and shippers, in contrast, had wide-ranging, dynamic mercantile interests and more cosmopolitan social relations.

Following the hardships of the Revolutionary War, this merchant class worked to put trans-Atlantic trade on a firm footing and also provided political leadership. Massachusetts' two leading traders, James Bowdoin and John Hancock, held the Governor's office for the entire decade 1780-1791. -

Economic Crisis: High taxes, mounting debt

In the first years of peacetime, the future of both the agrarian and commercial society appeared threatened by a strangling chain of debt which aggravated the depressed economy of the postwar years. Many of the farmers were veterans who had trudged home from the Revolution "with not a single month's pay" in their pockets, but only government certificates they had long since sold away to speculators. -

Massachusetts levies taxes, passes laws, and condemns insurgents, 1787

Adding to the farmers' postwar frustrations, heavy land taxes undermined the fragile financial structure of the hill towns. Farmers grew indignant as they watched the furniture, grain and livestock of their relatives and neighbors sold off for much less than their value. As they saw a brother, father or cousin haled to debtors' court, charged high legal fees, and threatened with prison, the free farmers of western and central Massachusetts feared they would be reduced to the status of tenant farmers. -

At first the farmers attempted to work within the framework of government, seeking only to modify it and (from their viewpoint) improve it. But by the autumn of 1786 state lawmakers had issued only small or token reforms, and these came too late to pacify the farmers, who needed immediate relief. With debtors' court still a reality, it now seemed to the farmers that redress lay only in open rebellion. -

Two typical rebels -- Daniel Shays and Jason Parmenter -

The nominal leader of the movement was Daniel Shays, 39, a farmer who had served at the Battle of Lexington, been distinguished for his gallantry at the Battle of Bunker Hill and seen action at the crucial Battle of Saratoga in 1770 and at Stony Point. Now, somewhat reluctantly, he was commanding insurgent actions at Springfield, and before long the name of Captain Shays became a battlecry for as many as nine thousand rebellious farmers throughout the disaffected areas of New England. -

Shays's followers had no uniforms except for the coats and hats that some had worn as Revolutionary soldiers. They identified themselves by wearing a sprig of hemlock (evergreen) in their hats. -

A typical soldier in Shays' army was Jason Parmenter, 51. In the Revolution, Parmenter had participated in the defense of Ticonderoga and was present at Burgoyne's surrender. When peace returned, Parmenter was elected constable and tax collector of his town. In this office, he witnessed the economic distress that was driving him and his townsmen to rally under Shays. -

-

Forcing debtors' courts to close, 1786

During the autumn of 1786, veterans like Shays and Parmenter organized groups of farmers into squads and companies in order to march upon the hated debtors' courts and force them to postpone their business.

Boston merchants and legislators viewed these court closings with rising fear for the very foundations of their society. In response to this alarm, the Congress of the Confederation authorized the raising of troops to combat the rebels, but the national government proved powerless to raise the financing. -

Finally, Massachusetts' governor James Bowdoin and other merchant leaders in Massachusetts used their own funds to field an army. -

The basic conflict

The Shays insurgents never imagined that their actions would lead to charges of treason against the republic. In fact, they naturally appealed to the republican principles they had fought for in 1776. "I earnestly stepped forth in defense of this country, and liberty is still the object I have in view," an insurgent leader wrote to the public. -

Eastern political leaders, on the other hand, believed that the gains of the Revolution were being undone by "knaves and thieves" who "intended tyranny." Governor Bowdoin warned that any interference with the legal system would "frustate the great end of government -- the security of life, liberty and property." -

In a new and precarious republic, the danger of anarchy -- bringing a regression to a Hobbesian state of nature -- appeared all too real. From the commercial viewpoint, the farmers' demands for a circulating paper currency would bring depreciation and fiscal chaos, while non-payment of state taxes meant that men of wealth who had lent large sums to the war effort would be "drained of cash" and would face bankruptcy instead of the economic expansion they had hoped for. As the year 1787 dawned in this atmosphere, it seemed Massachusetts was divided into two armed camps. Retreat, resistance, and exile, 1787

The critical point of the rebellion was Shays' march on the government arsenal at Springfield in January 1787, the only means of standing off troops who were advancing from Boston under General Benjamin Lincoln. At the arsenal, the defending militia commanded by General William Shepard unexpectedly fired their cannons into the ranks of the advancing rebels, killing four and wounding 20. -

Crying "murder" -- for the insurgent farmer-veterans never supposed their neighbors and fellow veterans would fire on them -- the Shays men retreated in disarray, pursued by Lincoln's government soldiers. -

Well into 1787, the farmers' resistance took the form of isolated flareups of violence against men such as lawyer and future Federalist statesman Theodore Sedgwick, who was briefly captured by those he called "violent desperadoes." Sedgwick's reaction was to organize an independent county force and defend his town against insurgent attacks, though his home was ransacked and his law apprentices taken hostage in their underclothes. -

But the rebellion was now broken. Shays himself fled to Vermont, not yet part of the union and therefore not bound to heed Massachusetts' appeals for extradition of offenders. Some other insurgents followed him there, including Jason Parmenter. -

Trials for treason, 1787

Shays' Rebellion was over, but Massachusetts' officially declared state of insurrection continued. A special court indicted more than 200 rebels -- including Parmenter, who had been caught returning to Massachusetts one night -- and prosecuted them in formal trials. Parmenter's court-appointed defenders included conservative attorney Caleb Strong, a prominent state senator who was almost as hostile to the rebellion as the prosecution. In April 1787, five Shays men charged with treason were condemned to hang. -

In the election of June 1787, Governor Bowdoin was roundly defeated by the state's most popular politician, John Hancock, famous signer of the Declaration. -

With a new administration in place, the question of clemency was now a symbolic issue debated by a divided public. General Lincoln himself, the subduer of Shays' Rebellion, came out in favor of mercy. On the other hand Samuel Adams, the influential Revolutionary patriot and head of the governor's advisory council, called for the execution of convicted traitors to the republic. -

Treason -- and murder?

The case of Jason Parmenter, awaiting execution in Northampton jail, was especially vexatious. Sentenced to hang for participating in Shays' attack on the Springfield arsenal, Parmenter separately was guilty of fatally shooting a government soldier -- inadvertently in the dark of night, he maintained. Perhaps he could be pardoned for marching on Springfield -- but what about the charge of murder?

The Hancock administration continued to hedge on this potentially explosive problem. At last a formula was devised which would equally dramatize the justice and the mercy of government: Parmenter and his fellow convicts were paraded at the gallows on June 21, 1787, before a large crowd of spectators -- and were reprieved only at the last instant. -

The rebellion and the Constitution

Shays' Rebellion had a generally unifying effect upon the supporters of a stronger national government, and it was a lesson frequently invoked on the floor of the Federal Convention during the summer of 1787. -

For George Washington, who gave the insurrection as a reason for his own attendance at the Philadelphia convention, "there could be no stronger evidence of the want of energy in our governments than these disorders." -

Massachusetts, its prestige in the union challenged, sent none other than Caleb Strong as one of its representatives to the Federal Convention, partly in order to signal to the nation that order was being restored -- for Strong was a conspicuously pro-government gentleman representing a notoriously unruly state. -

Shays' Rebellion became a recurring example in the debates among framers of the Constitution, encouraging some to favor the "Virginia plan" (which called for an unprecedented and powerful central government) over the alternative "New Jersey plan" (which seemed too favorable to state sovereignty). "The rebellion in Massachusetts is a warning, gentlemen," cautioned James Madison, proponent of the Virginia plan.

-

The Virginia plan -- the basis of a government that balances federal and state power, and balances the power among the states themselves -- carried by a vote of seven to three on June 19, 1787. The proposed Constitution of the United States, safeguarding the institution of property from financial disruption and from future taxpayer rebellions, was signed by 39 representatives of 12 states on September 17, 1787

The year 1788 brought an economic upsurge to Massachusetts which (as Samuel Eliot Morison wrote) "did more to salve the wounds of Shays' Rebellion than all the measures passed by the General Court [the Massachusetts government]." Nearly all Shaysites were reprieved or pardoned, although two were hanged (for burglary) in 1787. Daniel Shays was pardoned in 1788 and lived to an old age in New York state, as did Jason Parmenter in Vermont. -

Ratifying the Constitution, 1788

Significantly, the societal tensions of Shays' Rebellion were reflected in the ratification votes of the states most affected by the insurrection. By January 1788, five states had ratified the new Constitution, with Connecticut being the first in New England to do so.

But in Massachusetts, many opponents of ratification were former Shays rebels. After a considerable struggle, the vote was 187 in favor, 168 opposed. Massachusetts became the sixth state to ratify the Constitution, by a margin of 19 votes. -

After an equally close struggle, New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify the Constitution -- making it the law of the land -- on June 21, 1788. (However, Rhode Island needed to uphold state sovereignty in order for its paper money to have value. The state declined to ratify the Constitution 13 times in two years. Finally in 1790 -- one year into the presidency of George Washington -- Rhode Island approved the Constitution -- by a margin of two votes.)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.